And I Mean To Be One Too

There’s a hymn I love. It is unpretentious, earnest, and more profound than it first appears. It’s called I Sing a Song of the Saints of God, written in the 1920s by Lesbia Scott for her children. Though never adopted in official hymnals in her native England, it found a second life in the United States, especially among Episcopalians. Its charm lies in its accessibility—its refusal to treat sainthood as something otherworldly or reserved for spiritual elites. Instead, it insists that sainthood is ordinary and available to anyone willing to live a life of love and courage.

Here are the lyrics in full:

I Sing a Song of the Saints of God by Lesbia Scott

I sing a song of the saints of God, patient and brave and true, who toiled and fought and lived and died for the Lord they loved and knew. And one was a doctor, and one was a queen, and one was a shepherdess on the green: they were all of them saints of God, and I mean, God helping, to be one too.

They loved their Lord so dear, so dear, and God’s love made them strong; and they followed the right, for Jesus’ sake, the whole of their good lives long. And one was a soldier, and one was a priest, and one was slain by a fierce wild beast: and there’s not any reason, no, not the least, why I shouldn’t be one too.

They lived not only in ages past; there are hundreds of thousands still; the world is bright with the joyous saints who love to do Jesus’ will. You can meet them in school, or in lanes, or at sea, in church, or in trains, or in shops, or at tea; for the saints of God are just folk like me, and I mean to be one too.

That final stanza has always stayed with me. It reframes everything. “The saints of God are just folk like me.” Not paragons of virtue born with halos and flawless faith, but ordinary people who allowed the grace of God to work through them in their daily lives. People who told the truth when it was costly. Who gave more than was expected. Who noticed suffering and did not look away. Who loved with urgency and lived with purpose.

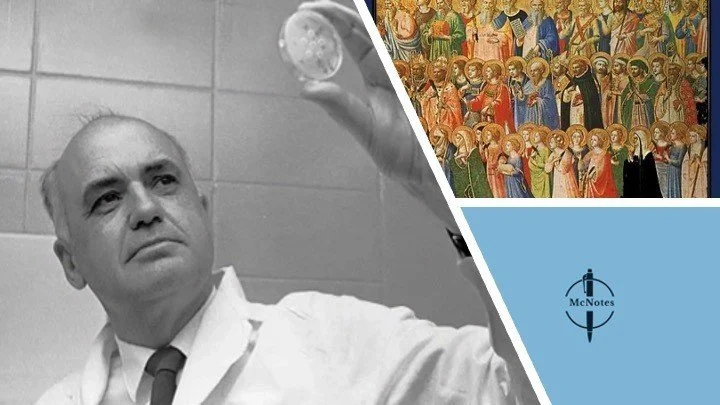

It is hard to think of a modern example that embodies this more fully than Dr. Maurice Hilleman.

Born in the bleak aftermath of the 1918 influenza pandemic, Hilleman came into the world on a struggling Montana farm. His mother died two days after giving birth to him, and he was raised by his uncle and aunt in conditions few of us today could imagine—without running water, electricity, or the promise of anything but hard work. He was one of eight children and grew up working on a chicken farm. No one looking at him then would have imagined he would become one of the most consequential figures in the history of public health.

But he did. Over his long career, Hilleman developed more than 40 vaccines. Of the fourteen vaccines given routinely to children in the United States today, eight were developed by him—measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, chickenpox, meningitis, and pneumonia. It is estimated that his work saves over 8 million lives every single year.

The scale of this is almost unfathomable. The world before vaccines was a world thick with grief. It was common for children to die from measles or complications from mumps. Rubella caused tens of thousands of miscarriages and congenital birth defects. Parents lived in quiet dread. Outbreaks swept through schools and neighborhoods like wildfires. Fevers brought panic, not just worry. Even common illnesses like chickenpox had fatal complications. It was a time when simply surviving childhood could feel miraculous. When Hilleman was born, one in five children died before reaching their fifth birthday.

Hilleman never romanticized this. He knew it for the horror it was. It is said that he kept a list in his pocket throughout most of his professional life. A simple scrap of paper, with the names of the diseases that killed the most children. Each time he developed a successful vaccine, he would take out the list, cross one off, and move on to the next. This was not theoretical for him. It was a war against deadly enemies, and he worked at a relentless, almost feverish pace to win it.

He did not stop with invention. He led the rapid rollout of vaccines through collaboration with pharmaceutical companies and government health agencies. He pushed back against bureaucratic inertia and scientific hesitation. His work was not just in the lab. It was in the systems he helped reform and in the lives he helped save. Even his family was part of it. When his daughter Jeryl Lynn came down with mumps, he collected a throat swab from her and used it to develop the very strain used in the mumps vaccine still administered today.

Despite all of this, Hilleman remains largely unknown. He did not win a Nobel Prize. He did not appear on television. He avoided the spotlight and disliked ceremony. His life was devoted to others, not to the promotion of self. He was, in every way that matters, a saint.

And yet today, his legacy is under quiet threat. Vaccination rates in some parts of the country have begun to fall. Misinformation, distrust, and politicization have begun to chip away at one of the greatest public health triumphs in history. Diseases we thought vanquished are returning—not because Hilleman failed, but because we are forgetting.

This is why the hymn matters. This is why the memory of people like Hilleman matters. Our children need stories like his. Not just because of the science, but because of the spirit behind it. They need to know that heroism is not reserved for the powerful. They need to know that ordinary people can lead extraordinary lives of service. They need to know that they, too, can aspire to be saints.

In a world that tells them greatness is about attention, platform, or applause, we must offer another vision. One that sees greatness in sacrifice, in integrity, in kindness. One that teaches them they don’t need to wait to be adults, or perfect, or famous, to make a difference. They can begin now—in the way they treat a classmate, in the effort they give to their work, in the courage they show to speak up or do what’s right when it’s hard. These are the habits of sainthood, and they can be practiced young.

The saints of God are just folk like me. Just folk like you. Just folk like the children we teach.

And, God helping, I mean to be one too.